The branches snapped back as the prisoners fought their way down the trail. Behind them, Betty Olsen could hear a lagging prisoner being beaten. She closed her eyes briefly and prayed for the prisoner. “Lord, give him strength.” And then she forced herself to take yet another step. She was a long way from her college classrooms in New York. And she had never felt closer to Christ.

The branches snapped back as the prisoners fought their way down the trail. Behind them, Betty Olsen could hear a lagging prisoner being beaten. She closed her eyes briefly and prayed for the prisoner. “Lord, give him strength.” And then she forced herself to take yet another step. She was a long way from her college classrooms in New York. And she had never felt closer to Christ.

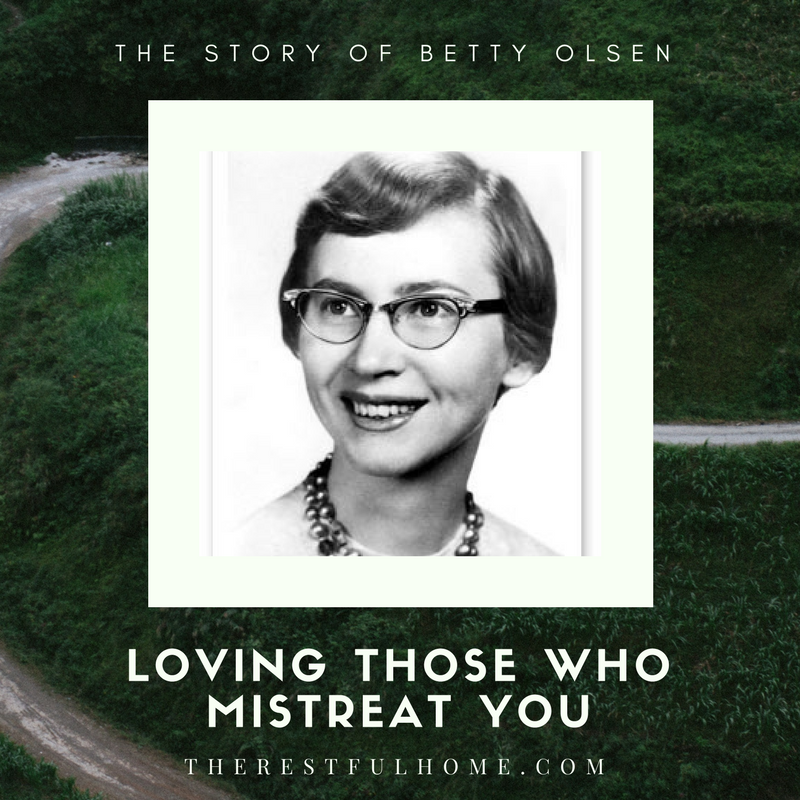

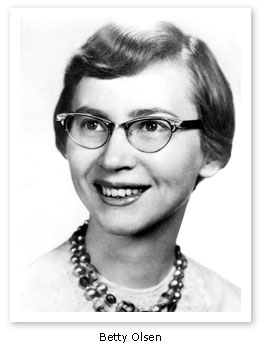

Most of us have never even heard her name. Betty Olsen sounds like the name of a shortbread-baking church pianist in Minnesota or North Dakota, not a courageous missionary in the jungles of war-torn Vietnam. But that’s just who she became. And her biography is worth spending some time with, as we challenge ourselves to follow the Lord no matter what our circumstances.

Betty didn’t always have a strong faith–she struggled through depression and doubt, like many of us have at times in our lives. But once she had settled in her heart that God’s will came first, her every step in life followed suit.

Betty Ann Olsen’s Early Years

Betty didn’t have a normal upbringing. She was born in 1934 in Ivory Coast, Africa to missionary parents. Most of her childhood was spent away from her family at a missionary-kid boarding school 800 miles away–standard procedure for the time. However, during her high school years, she decided she wanted to follow in her parents’ footsteps and become a missionary. She trained as a nurse and then as a missionary. In her senior year of college that Betty began to have doubts, though.

She felt far away from God, and no counselor seemed able to help. She said despairingly to God, “If this is all there is to the Christian life, then I don’t want it.”

Eventually, she found an answer that gave her peace: “I had to really want the Lord’s will and His best and truly repent and seek Him with my whole heart before He would help me.”

Vietnam: In the Center of the Lord’s Will

Reunited with her Lord, Betty was freshly energized to go serve Him in a place where very few had heard the name of Jesus: Vietnam. Vietnam in the early 60s was a very dangerous place to be–right in the middle of the 10-year Vietnam War (1955-75), there was no such thing as a bystander. Everyone became involved in the conflict, whether by choice or not.

Betty joined The Alliance, a missionary organization that had been active in Vietnam since the early 1900s, and headed to Banmethout, Vietnam. She moved there in December of 1964 to work at the hospital for people with leprosy, writing in her testimony the following words:

“Most of the people that I have told about going to Vietnam are greatly concerned, and I appreciate this; however, I am not concerned, and I am very much at peace. I know that I may never come back, but I know that I am in the center of the Lord’s will and Vietnam is the place for me.”

Three missionaries in that region had already been abducted by the Vietcong, so Betty knew that was a possibility. But every day, she had work to do among her patients, and she continued in spite of the war happening around them.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘I am not concerned, and I am very much at peace. I know that I may never come back, but I know that I am in the center of the Lord’s will and Vietnam is the place for me.’ –Betty Olsen, Martyr” quote=”‘I am not concerned, and I am very much at peace. I know that I may never come back, but I know that I am in the center of the Lord’s will and Vietnam is the place for me.’ –Betty Olsen, Martyr”]

The Long March

In late January of 1968, just over three years since Betty’s arrival, the Vietcong attacked the compound and leprosarium. Several missionaries were killed. Betty and Wycliffe linguist Henry Blood (“Hank”) were attempting to escape on Feb. 1 when they were captured by the Vietcong. They and fellow prisoner, humanitarian Mike Benge, spent a month in cages at a POW camp a day’s walk away from Banmethout. Their only food was boiled manioc (a starchy root very low in nutrition).

Fearing rescue of their prisoners or air strikes by the Americans, the Vietcong began moving their prisoners rapidly. They spent 12-14 hour days marching through mountainous jungles.

From the POW network comes Mike Benge’s description of their long march:

“For months Olsen, Blood and Benge were chained together and moved north from

one encampment to another, moving over 200 miles through the mountainous

jungles. The trip was grueling and took its toll on the prisoners. They were

physically depleted, sick from dysentery and malnutrition; beset by fungus,

infection, leeches and ulcerated sores.Mike Benge contracted cerebral malaria and nearly died. He credits Olsen with keeping him alive. She forced him to rouse from his delirium to eat and drink water and rice soup. Mike Benge describes Olsen as “a Katherine Hepburn type…[with] an extra bit of grit.”

During that summer (the rainy season), the prisoners were constantly in the rain, whether walking or lying down to sleep. Missionary Hank Blood died of pneumonia around July and the Vietcong buried him along the trail, allowing Betty to conduct a simple graveside service for him. But they weren’t allowed to stop for long. By now, Betty and Mike were both covered with sores and had severe gum disease from malnutrition, causing their teeth to begin falling out. To keep their spirits up, they would talk about their favorite restaurants and how they would visit them together when they got home. Sometimes, the Vietcong would stop the group of prisoners for a few days of rest, but then they would start moving again.

It’s “Up to God to Decide” When We Die

Betty constantly tried to keep up the spirits of the other prisoners, especially the Vietnamese Christians who had also been captured. Although she wasn’t given much food, she would often save most of it to give to them. When Mike was at his sickest, she would also share with him (pretending she wasn’t hungry enough to eat all her food) and pray for him.

The Vietcong were moving them toward Cambodia, their “promised land.” As Betty grew weaker, the Vietcong would kick and beat her to force her to keep moving. Mike tried to stand up for her; they beat him with their rifle butts. Both of the American prisoners could hardly walk. Mike’s description of walking when severely malnourished:

“…we’d have difficulty lifting our legs. To step over a log, for instance, I’d have to lean down and with my hands lift each of my legs over one at a time.” [“On Being Starved“]

More of Mike’s memories, from an article written by him about the intrepid missionary who had become his friend and had saved his life:

By November 1968, the lack of food and our constant moving had worn Betty down. One day, the NVA separated us, but by evening, we were reunited. Betty said they had kicked and dragged her the whole day, and she couldn’t go on. I told the NVA officer-in-charge that we refused to go any further until Betty was given some good food and allowed to rest. They jacked shells into the chambers of their AKs and put them against our heads. They said that as civilians we were of no value as POWs and only took rice from the mouths of their soldiers. Betty’s retort was that it was up to God, not them, to decide when we would die. It seemed to confuse them. They lowered their weapons and said we were crazy.

Fullness of Joy

Near the border, they found gardens and streams with plenty of fish. The Vietcong didn’t allow prisoners to gather food from the gardens, however. The prisoners gathered bamboo shoots, but didn’t know that the bamboo needed to be cooked twice. The resulting stomach cramps and diarrhea further weakened Betty’s fragile, starving body. “Unable to get out of her hammock, Betty lay for three days in her own defecation before she died. They wouldn’t even allow me to clean her up,” Mike remembered.

The combination of disease and abuse killed Betty Olsen before she ever reached the final POW camp. When Mike arrived at the camp, the other prisoners thought he was in his seventies because of his gaunt body and newly white hair. He was 33 years old. He had dropped from 160 pounds to less than 100. Mike still had several years of torture left to survive; Betty, however, had already gone to be with the Lord Jesus, where she had “fullness of joy” and no more pain or shame.

Loving Those Who Mistreat Us

Not all of us will live in war-torn countries. Not all of us, thank God, are required to undergo the sufferings that Betty Olsen faced. But all of us can learn from her attitude. In the face of overwhelming, unimaginable torture and pain, Betty chose to focus on others. When starving to death, she shared the little food she had. As she suffered in cages or on long, rough trails, she prayed for others. In the face of incredible evil, she chose to love. Mike Benge remembered her attitude long after she died.

“She never showed any bitterness or resentment,” he said. “To the end, she loved the ones who mistreated her.”

She had the attitude of Christ, who on the cross said, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” (Luke 22:34)

After reading a story like Betty’s, I’m incredibly convicted by the petty resentments I’ve held in the past. How can I choose to be bitter or resentful over anything? Not only Christ, who is perfect, but also his imperfect follower, Betty, who trusted in Christ’s perfection and grace, could extend such mercy and forgiveness. May we follow their example.

To Learn more about Betty Olsen:

Read the Alliance’s short biography of Betty, or read the thorough account on the POW network.

You can also read Betty Olsen’s story in Some Gave All: Four Stories of Missionary Martyrs. (Look for the paperback version.)

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘To the end, she loved the ones who mistreated her.’ Betty Olsen, missionary martyr and nurse #martyr #truelove #faith #eternalview ” quote=”‘To the end, she loved the ones who mistreated her.’ Betty Olsen, missionary martyr and nurse”]

Please share this story so that more can be inspired by Betty’s example of serving Christ.

You may also enjoy reading the story of Marie Durand.

: a favorite place to walk when we can!

Once

: a favorite place to walk when we can!

Once

![The first photos are of my parents’ sprawling rural Arkansas garden. The last is of my tiny little beds in the big city. Plants bring life to even the smallest corner!

I’ve been reading some beautiful fiction this year, and I just posted a review of a book by one of my favorite authors, Leif Enger. (https://therestfulhome.com/brave-young-handsome-review/ in your browser, or click on the link in my Instagram profile) If you don’t have time to read the book, though, here’s just a quote or two for your enjoyment:

🎼

“Death arrived easy as the train; [he] just climbed aboard, like the capable traveler he was.”

🛤️

On riding a horse: “You are a feeble and tenuous being; the only thing a horse wants from you is your absence.” 🐎 😄

#quotes #leifenger #amreading #gardens #gardening](https://scontent-atl3-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t39.30808-6/468657020_18342474787176025_4442629541396867851_n.jpg?_nc_cat=108&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=DEja6UP2ct4Q7kNvgEYJxCM&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-atl3-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=AA4bBsvQ_JpqZXLUPUTpTC8&oh=00_AYCjI9LUx-cJxe6cu0n7H1Gounaz92aBlTrQacnKut8umg&oe=67567CAB)